Using a human-centered design process, we created a voice and movement controlled group game that teaches people about extinct animals, their role in distinction and promotes behavioural change. A group of 3 people collaborates to steer an endangered animal safely through its habitat (by making noises), while avoiding harmful objects and collecting items that positively contribute to this animals’ life (by moving). *This project was part of my Masters’ HCI at the University College of London, where we were asked to submit an innovative, boundary-pushing game. We submitted to the CHI2020 Student Game Competition, where our paper was accepted and we were selected as one of the three winners.

Team

4 MSc HCI UCL students (including myself)

My Role

Conducting primary and secondary research together as well as exploring ideas through sketching, creating multiple interactive prototypes and iterative testing.

Timeline

October - December 2019

THIS VIDEO SHOWS HOW WE DESIGNED THE GAME

THIS VIDEO SHOWS A TRAILER OF HOW THE GAME IS PLAYED IN OUR FINAL DESIGN

The problem

Research shows that animal extinction has never been this fast-paced. Many people are aware of global warming and really interested in nature but lack knowledge on how they actually can make a difference and change their behaviour in daily life. Existing environmental games seem to show potential in supporting behavioural change, but contain too much information and are found not immersive enough, presumably limiting their effectiveness.

Challenge

How can we raise awareness and build knowledge about limiting animal extinction through a playful and engaging game experience that teaches concrete actions? We wanted to reach a wide audience interested in helping endangered animals and decided to locate our game in public educational spaces. We found that mostly Young Creatives visited these places and decided to design initially for this user group as they also may pass on their knowledge as potential parents of future generations.

Research and requirements

A review of previous research on successful games informed initial requirements. To verify these requirements with our user group, we surveyed 65 Young Creatives on their preferences regarding gaming, museums, input modalities and technology usage. We also asked about their interest in the environment, extinction and education in this. Results indicated that our user group experienced difficulties in behaving ecologically, wanted to learn more about helping endangered animals, and were hesitant in playing voice-controlled games.

Based on these results and existing research, we established the design requirements. The game should:

- Support social interaction, experiential learning and a feeling of meaningfulness

- Be engaging to increase empathy and awareness

- Be played as a group to increase motivation, engagement and trigger collective action

- Potentially be voice controlled, as this was found highly engaging and innovative, while never been used in group contexts

- Potentially be controlled by movement to enhance expression of emotions with other players, making it more meaningful and engaging

- Be played with smartphones (to easily access multiple sensors as input modalities), in combination with a shared display

Using our findings, we created a persona representing the needs and pain points of our users to support us in design decisions.

Carving out our concept

First, we individually brainstormed ideas of potential games and approaches. We evaluated these ideas using a 2x2 matrix on feasibility and novelty.

Eventually, we combined components of multiple ideas which led to our idea of the ‘follow the path’ style game where a group of players navigate an animal through its habitat, collecting and avoiding meaningful items. Our idea was to teach people how to collaborate in taking action against animal extinction and provide concrete and recognisable examples. The objects were related to everyday items players use, and running across harmful ones decreased the ‘health level’ of the animal to increase awareness and empathy of the actual impact and facilitate transition to real-life actions. ‘Collect items’ represented the opposite, showing concrete solutions players could implement in their own life.

However, we were not sure about the input modalities, as survey results showed hesitation around voice-input by our user group while in earlier research this was truly enjoyed. We decided to do early user tests to explore different modes of interacting with the game.

Early user tests

To conduct the tests, we created a quick paper prototype of our game idea and used our sketches to explain the game and provide context. We asked a group of 3 people to play the game using different interactions, while one of us mocked the movements of the animal in the game.

Our user tests showed that players liked the general idea of our game and particularly enjoyed the social aspect of steering the animal together and having individual roles to control directions by their voice. Jumping together to avoid items was found very engaging, as it evoked a feeling or demonstrating against animal extinction. However, an interaction to collect items was missing, causing less awareness on helpful items.

Refining our game

As our early usertest had largely validated our game idea, we refined our game concept and explored how we could enhance education and transition of behaviour after the game. We individually sketched our ideas of the entire game journey in multiple storyboards (e.g. encountering, getting information about animals, starting the game, levels, post-game interactions). We assembled all sketches, silently voted them individually and created a timeline together afterwards containing the best ideas.

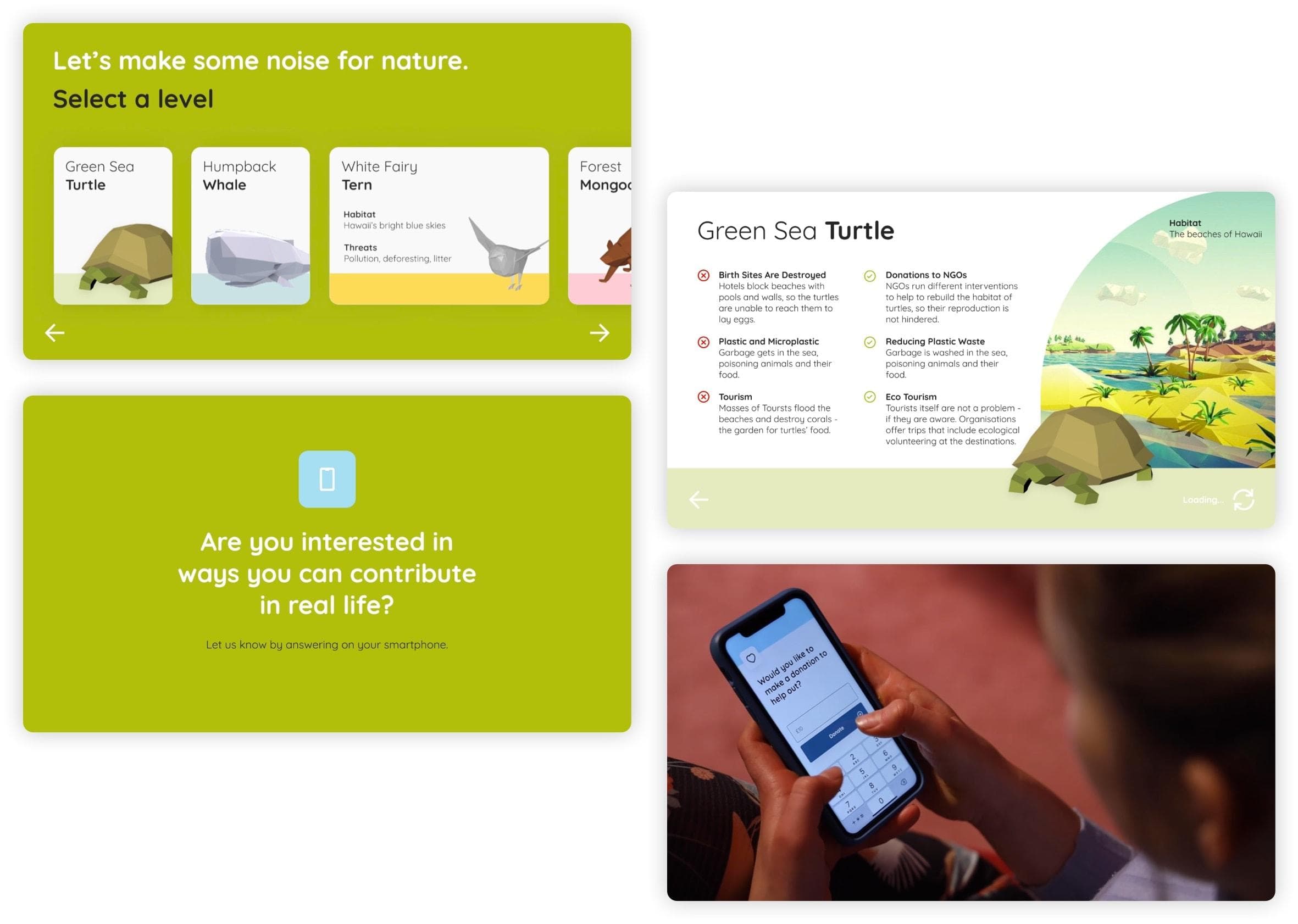

We then created wireframes of important interactions before and after the game, such as information about the animal, choosing your favourite animal, and receiving practical tips a week after having played the game. These wireframes were discussed with five participants and refined.

In parallel, a teammember created a high fidelity prototype of the game itself in Unity and combined this with our refined wireframes to allow testing of the whole game interaction.

Evaluationg our game

We conducted a final Wizard-of-Oz user test with three participants that played the game on a big screen from beginning to end, while we secretly controlled the animal with a keyboard. Again participants controlled the animal with their voice, but now collaborated in jumping and bending movements to avoid and collect. Players said that the game itself forced them “to move physically and mentally to help the animal” and was challenging and fun. They also found the information about the animal really useful as well as the practical post-game tips on helping the animal after the game.

Learnings and outcomes

- The game seemed to lead to higher awareness and willingness in players to take action to protect endangered animals. If we had more time, I would have liked to test its actual effect on behavioural change and how to ameliorate this by personalising the collect/avoid objects

- I learned to not discard good ideas before testing it on users as Young Creatives first seemed reluctant of playing games with their voice but loved it during user tests

- We became finalists of the CHI2020 Student Game Competition!